“There is little pride in writers. They know they are human and shall some day die and be forgotten. Knowing all this a writer is gentle and kindly where another man is severe and unkind.”

― William Saroyan

William Saroyan Biography

This man with a non-Armenian name “William” and an Armenian surname was born in 1908, August 31 in Fresno, California, in a poor family of Armenian immigrants from Bitlis, Turkey.

The American – Armenian William, at the age of three, together with his brother Henry and his sisters Zabel and Cozette spent several years at the Fred Finch Orphanage in Oakland right after their father’s (Armenak Saroyan) death.

After five years, the family reunited in Fresno. His mother, Tagoohi, started to work at a cannery. William Saroyan’s formidable maternal grandmother Lucy (also widowed), who had a great influence on him, joined the household.

Armenak Saroyan was an enduring source of motivation and encouragement for his son, even though William had quite blurry memories of him. Armenak was a writer as well.

His son, William, meant to succeed and continue the unfinished path of his father.

After his mother, Tagoohi showed him some writings of his father, it motivated him to become a writer too.

Many of Saroyan’s stories represent his childhood experiences among the Armenian-American fruit growers of the San Joaquin Valley or dealt with the rootlessness of the immigrant.

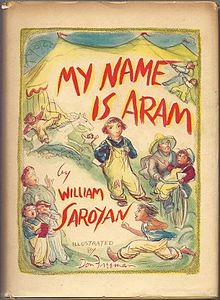

First edition (publ. Harcourt Brace) Illustrated by Don Freeman

The short story collection “My Name is Aram” (1940), an international bestseller, was about a young boy and the colorful characters of his immigrant family.

Saroyan left the school early. His school work was too slow. There was constant friction because of boredom and frequent reminders that he was a son of an immigrant. He also did not have college in his plans.

When he was 12, he, by chance, read the Guy de Maupassant story “The Bell”. After that, his desire to become a writer started to get deeper. He became a frequent visitor to Fresno’s public library. He learned to touch-type at the Technical School as well.

Saroyan left school at 15 and continued his education on his own by reading, writing and supporting himself by taking various jobs, such as working as an office manager for the San Francisco Telegraph Company.

At the age of 18, Saroyan started to think that Fresno was too small for him. He wanted to leave and chase his destiny.

So, his first stop was Los Angeles, where the hopeless William joined the National Guard. However, it lasted only for two weeks.

A short story of his was accepted by The Overland Monthly (a western magazine which in its day had published the work of such famous writers as Jack London and Ambrose Bierce).

A year after being outside Fresno, Saroyan took a Greyhound Bus to New York. Unfortunately, he discovered on arrival that his suitcase was now in New Orleans by mistake. And the worst part is that all his money was there… After about six months, he returned to California. This time more mature, wiser and quite embarrassed, but meantime, he was glad to clear out the expectation that he would suddenly write something which would be successful enough to bring him instant fame.

An Armenian journal “Hairenik” published his work in 1933. William Saroyan, however, was getting tired of refusals in other journals and magazines. He was about to stop sending stories to the “idiot editors of insignificant magazines.”

In 1934 though, he sent to “Story”(a national magazine) “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze,” a story about a young writer who starves to death, with dignity.

The editors of the magazine were looking for a new, outstanding writing talent. They accepted Saroyan’s story in the end and paid fifteen dollars.

In After Thirty Years: The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze (1964) he tells his readers that he informed the editors that during the whole January (1934) he would send them a new story every single day.

In the middle of the month, a telegram arrived from the editors of the magazine saying that his stories caught great interest and that he should keep sending.

This acceptance of him as a writer was a great success, and hence, made a huge impact on his life.

His stories soon started appearing in such magazines as “The American Mercury”, “Harper’s”, “Scribner’s”, ” The Yale Review” and “The Atlantic Monthly”.

In October 1934, Random Hous(the largest general-interest paperback publisher in the world) published “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze” and “Other Stories”. The book, as a collection of short stories, was a best-seller.

Soon he planned to visit Europe together with the land of his descendants.

The impact of his first journey on his life, according to a lot of references to it in his later writings, was huge. During his trip, in Moscow, he met the famous Armenian poet Yeghishe Charentz.

Throughout his life, Saroyan visited Armenia four times, in 1935, 1960, 1976 and 1978, and even saw his play “My Heart’s in the Highlands” in Yerevan theatre after G. Sundukyan staged by Vardan Adjemyan. Arno Babadjanyan wrote the music.

Victor Ambartsumian and William Saroyan

More collections of short stories: “Inhale and Exhale”, “Three Times Three”, “Little Children”, “The Trouble with Tigers”, “Peace, It’s Wonderful”. He wrote them in a variety of styles and moods.

His most successful early collection was “My Name Is Aram” (1940). It is a book which represents the Armenians of his hometown in the days of his boyhood.

Career

William Saroyan’s career as a playwright began with his first play, “My Heart’s in the Highlands” in 1939, produced by the Group Theatre. His greatest theatrical success, “The Time of Your Life” quickly followed the play. In 1940, William Saroyan rejected the Pulitzer Prize for his play “The Time of Your Life” since it was “no more great or good” than anything else he had written.

A series of Broadway productions (Love’s Old Sweet Song, The Beautiful People, Across the Board on Tomorrow Morning, Talking to You, Hello Out There) followed The Time of Your Life. For a period in 1941, he established a Saroyan Theatre at the Belasco.

In 1941 he took time off from his theatre activities to write a film scenario in Hollywood, The Human Comedy. He sold the script to MGM. for sixty thousand dollars. Then he offered to buy it back for a larger sum when they refused his demand to produce and direct the film himself. A trade paper denounced the studio when it declined.

The novel-turned-movie starring Mickey Rooney was a hit and won the Academy Award for best picture and original story for the screenplay. But it was hard to Saroyan’s liking. He turned the script into a novel, which became his most successful book.

In October 1942, during the WWII, Saroyan joined the army although he was a pacifist. His absence from Broadway during the war was damaging his career as a playwright. After the war, public interest in his works was decreasing due to changes in opinion and taste.

The Cave Dwellers was the one exception to his exile from New York. The play opened in 1957.

Though the decrease in interest in his works, William Saroyan remained a popular figure and continued to write. He began to write in the genre of memoir, including A Bicycle Rider of Beverly Hills (1952) and Short Drive, Sweet Chariot (1966). His last major book Obituaries (1979) received a National Book Award nomination.

- Paris 1973

- William Saroyan standing on his balcony holding a piece of rock from Armenia.

- William Saroyan

In Paris, in desperation, he wrote “The Assyrian”. This long story is about a dying writer, who is on his way his homeland to which he feels drawn. The story became the basis of a new collection.

Personal life

Early in the following year, he married Carol Marcus, a young socialite and a friend of Oona O’Neill. They had two children Aram and Lucy. After the birth of their son Aram, Saroyan had to go to England. After six years, however, William and Carol divorced. Then they remarried in 1951, but it was no success. They divorced for the second and final time two years later. The marriage, especially in its final stages, had been a costly and a killing experience. He was head-over-heels in debt to the Tax Collector.

His two novels, “Rock Wagram” and “The Laughing Matter”, hold the major theme of marriage breakdown. He also wrote a shorter fantasy work “Tracy’s Tiger”. None of these was commercially successful, but soon afterward he had a surprise worldwide hit with a pop song, ‘C’mon-a My House,’. The singer is Rosemary Clooney.

Saroyan most likely never really recovered from his unhappy marriage and the three wasted years in the army. In his fifties, after moving to Malibu, he regained his soul sufficiently.

In 1952 he published “The Bicycle Rider in Beverly Hills”. It was the first of his several book-length experiments in autobiography. A warm-hearted novel of the theatre (written for his daughter and serialized in the Saturday Evening Post), “Mama, I Love You”, a new collection of short stories “The Whole Voyald” and a book for his son “Papa, You’re Crazy” followed the book.

He had another play on Broadway, The Cave Dwellers, in 1957, and there were a number of television productions and adaptations of his works.

Meantime, he was publishing short stories and articles in the usual wide variety of magazines and journals. During the six years at Malibu, he earned around a quarter of a million dollars. But these earning did nothing to improve his tax situation; the debt remained.

He had an invitation to write an autobiography. Believing he would finally pay his debts, he produced the autobiographical work, Here Comes, There Goes, You Know Who. But by his own admission, the book did poorly.

Amongst his other activities in the early sixties, he created Sam, the Highest Jumper of Them All with Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop in London, after admiring its production of Brendan Behan’s The Hostage. Two novels followed. Boys and Girls Together and One Day in the Afternoon of the World.

Then in 1964, thirty years after the publication of his first book, he repeated his early effort of writing a new story or piece each day for a whole month, keeping at the same time a daily journal in which he discussed his present life and work in relation to January 1934. He had it published alongside the original stories as After Thirty Years: The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze.

Meanwhile, his plays were highly successful in eastern Europe, especially in Czechoslovakia.

By 1967, he was at last able to declare in “Days of Life and Death and Escape to the Moon”:

‘I’m free… I’ve paid all debts, I’m earning a living.’

In the late sixties, he finally started to “filter” the mass of the works he had written through the years which had appeared only in magazines or newspapers. The result was an entertaining collection of articles, essays, short stories, memoirs, poems and short plays, each with a specially written introduction.

Indulging his fondness for long titles to the full, he called the collection “I used to Believe I Had Forever, Now I’m Not So Sure”.

In his last book of the sixties, he used the autobiographical device of writing a series of ‘letters’ to various people, eminent and otherwise and most now dead, who had either influenced him or remained in his memory for some important reason. He called the book Letters from 74 rue Taitbout, or, Don’t Go But If You Must Say Hello to Everybody.

Next came Places Where I’ve Done Time (1972). In this one, he used the theme of places that were important in his life. Other works were Sons Come and Go, Mothers Hang in Forever (1976) and Chance Meetings (1978), which is about the sweet memories of some of the more obscure people he had met.

He had always produced a great deal of material that he never got around to publishing. A significant part of his output remained unprinted. His work was still very much in demand in Europe with stage and television productions of his plays in recent years in Czechoslovakia, Romania, Finland, Spain, Germany, and Poland. The Cave Dwellers continues to be a particular favorite.

His last published book was Obituaries (1979). Latterly the critics were finding much to admire in his work. Obituaries were accorded a generous attention in The New York Times Book Review.

William Saroyan once said that to write was for him simply to stay alive in an interesting way. His career lasted nearly half a century. Through the good times and the bad, he remained a writer in the purest sense, writing almost invariably out of himself, in the manner of a poet, with an only surface commitment to the orthodox literary forms.

His experience with his father’s death at a young age, his time spent in the orphanage, and in later years, his formal schooling, created the “joyous sorrow” which characterizes Saroyan’s works.

He sought in his fictional work to dispense with the device of emotionality or spurious excitement. Nor the creation of strong, memorable characters interested him. Speaking of a novel sent to him by a publisher, he said it wasn’t bad, but it was about specific people in that peculiarly specific way that makes a novel meaningless.

Saroyan barely ever consulted doctors. He thought that the fight against illness and death are personal struggles with God (the Witness), Fate or Bad Luck.

When he visited Europe for the last time in 1980, however, doctors diagnosed him with cancer.

He in 1981 he was buried in Fresno. However, according to his will, a part of his heart was buried in far-away Armenia, at the feet of Ararat, not far from Lake Van and town of Bitlis – the homeland of his parents.

Now a part of Willam Saroyan’s heart rests in peace among other notable Armenians in the Pantheon of Greats in Yerevan.

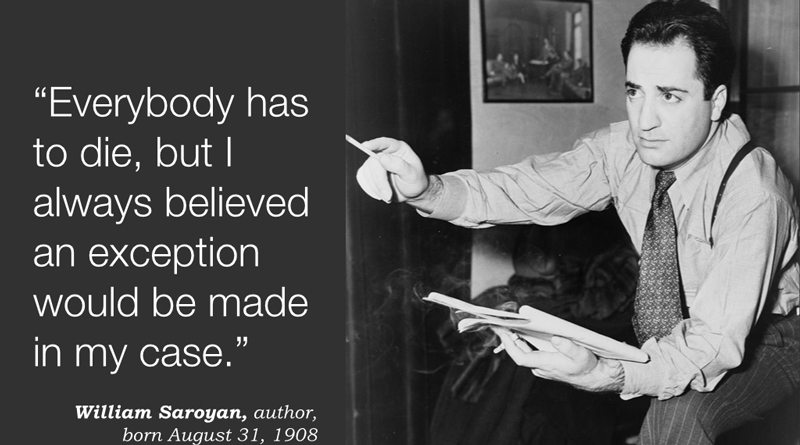

Five days before he died in May 1981, at the Veterans Hospital in Fresno, he telephoned a posthumous statement to the Associated Press:

‘Everybody has got to die, but I have always believed an exception would be made in my case. Now what?’

The New York Times described him as ‘an orphan hurt by a sense of rejection, craving love and bursting with talent.’ The Times in London felt that his reputation might come to rest on his later experiments with autobiography. The Time magazine (an old enemy) said that ‘the ease and charm of many of his stories will continue to inspire young writers. It is a legacy beyond criticism.’

Starting as a postman, William Saroyan became someone whose name is mentioned among such great American writers as Hemingway, Steinbeck, Faulkner, and Caldwell.

More than 30 years have passed since he left this earth, and there is no one to be able to fill his place in the literary world.

His own words describing himself:

“Although I write in English, and despite the fact that I’m from America, I consider myself an Armenian writer. The words I use are in English, the surroundings I write about are American, but the soul, which makes me write, is Armenian. This means I am an Armenian writer and deeply love the honor of being a part of the family of Armenian writers.”

Leave a Comment